Ideas for Addressing BVD in Your Dairy Herd

By Tom Shelton, M.S., D.V.M., Merck Animal Health, and Michael Coe, D.V.M., Ph.D., Animal Profiling International, for Progressive Dairyman

Editor’s note: This article is the final article of a three-part series.

Strategies to protect your investment

Chronic immunosuppressive diseases have a significant economic impact on many areas of a dairy. In the case of persistently infected (PI) cows, they often cull themselves early for a number of health or reproductive reasons, but it’s not unusual to find second-lactation cows that are still milking.

Collectively, these subclinical cows are quietly infecting their herdmates and progeny, tallying a significant cost to the dairy.

In this three-part series, our goal has been to provide perspectives and ideas on how to address bovine viral diarrhea (BVD) and related issues in dairy herds.

In the first article, we compared National Animal Health Monitoring System (NAHMS) bulk milk data with a more recent survey, which found 28 percent of herds greater than 500 cows BVD-positive with at least one BVD-PI positive cow. The 2007 NAHMS data reported 12.8 percent positive herds tested.

In the second article, we looked at costs associated with removing BVD-PI animals from herds identified as BVD-positive from bulk tank milk sampling. We also addressed the economics of subclinical BVD in herds versus elimination. The example presented a 6,000-cow dairy that identified and removed BVD-PI cows from the herd within 28 days and individually tested 625 animals for an average total herd cost of $0.55 per head.

In this final article, we’ll review what to expect as you work to eliminate BVD-PI cows, including the expected number of BVD-PI animals, testing do’s and don’ts, common human and laboratory pitfalls, and the impact of BVD congenitally infected (CI) protection of animals.

We’ll also discuss bovine leukemia virus (BLV) and Johne’s disease, which negatively affect herd health, production and annual profits but can be managed with a well-designed bulk milk disease monitoring program.

How many PI animals will I find?

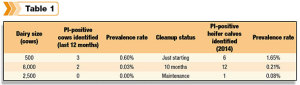

In our experience, BVD-PI prevalence in lactating herds with positive bulk tank results range from 0.02 percent to 0.11 percent, with an average of 0.05 percent. Let’s look at three dairies ranging from 500 to 6,000 head for more perspective. As shown in Table 1, the BVD-PI prevalence in heifer calves ranges from 0.08 percent to 1.65 percent, depending on the herd’s cleanup status (Table 1).

Eight months into a cleanup, the 6,000-cow dairy had tested 5,731 heifers and identified 12 (0.21 percent) additional BVD-PI animals. Along with routine bulk tank testing, the dams of the BVD-PI-positive heifers were tested to confirm their PI status.

The smallest dairy, with a 1.65 percent incidence, is an extreme example of what can happen without routine testing and when BVD-PI animals are present. Conversely, the 2,500-cow dairy illustrates what can be accomplished when you identify and remove all BVD-PI cows and heifers and work with your veterinarian to incorporate BVD-PI testing into a disease control program.

What about off-site heifers?

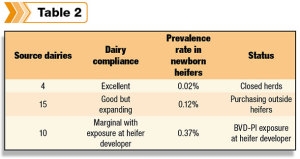

How replacement heifers are raised can influence their future BVD-PI status. Here are three examples of calf ranches that specialize in heifer development and, for several years, have tested all incoming heifers. The BVD-PI prevalence in newly received heifer calves for these operations ranges from 0.02 percent to 0.37 percent (Table 2).

The first calf ranch has excellent cooperation and coordination with the dairies it supplies, as well as with the developer that raises the heifers from 400 pounds to springing heifers. It essentially functions as a closed herd for disease management.

The second ranch has good cooperation with all 15 dairies. However, several are purchasing outside cattle to expand their herds, which has resulted in more BVD-PI calves.

In the third example, a couple of the ranch’s source dairies develop heifers in a separated facility, but most have not implemented a BVD-PI testing program. As a result, a large number of BVD-PI heifers are born and return to the ranch, continuing the exposure cycle and requiring their removal to protect the other calves.

Tips for sampling success

To implement a successful BVD-PI cleanup program, you must start with accurate sample collection and identification. We offer the following tips:

•Use permanent markers to label sample containers.

•Maintain one sample per container. Ensure it’s well sealed and padded.

•Print ID numbers carefully to prevent inaccurate results.

•Use preservative tablets or freeze the milk samples.

•Protect sample containers from moisture, as ice packs and frozen samples will sweat.

•Keep ear notch and blood samples cool after collection and during shipping.

CI adds another dimension

In addition to the BVD-PI animal, another condition known as congenital infection can occur with a wide range of consequences. These are unborn calves that have been infected after the immunological grace period of 45 to 120 days of gestation. When infection occurs before 45 days, the fetus will be lost. Infection after 120 days can produce congenital defects as well as fetal loss.

Perhaps of more economic consequence are calves infected after developing immune response to the virus and born looking normal but having BVD titers. These calves are identified by drawing serum before receiving colostrum and maternal antibodies from the dam. If they have BVD-specific titers greater than 1-to-4, they have evidence of being infected in utero.

Studies following these CI-positive animals forward have found a 2.5 times increase in disease incidence and delayed conception. Beef steers have shown similar health consequences along with reduced performance on feed.

In a survey of several large Western dairies, CI calves exceeded PI calves by a factor of at least 10. So, for a PI rate of 0.3 percent (three per 1,000), the CI rate may be greater than 10 to 20 times (three to six per 100). But we need more research to determine the exact negative economic consequences of endemic BVD within a herd from both PI as well as CI animals.

Bulk tank milk model

The bulk tank screening program described in these articles for BVD-PI animals provides a model to address other immunosuppressive diseases as well. In a survey, bulk tank sampling revealed that 80 percent of the dairies tested have a high enough prevalence of BLV-infected cows to be identified as a positive herd.

Johne’s disease tends to have relatively low prevalence, especially in well-managed herds that pasteurize colostrum and waste milk fed to calves. However, dairies with a relatively high Johne’s prevalence will test positive at the bulk tank level, thereby identifying at-risk operations. Approximately 10 percent of the tested dairies fell into this category.

The take-home message is that we can economically identify diseases like BVD, Johne’s and BLV that often don’t present as clinical disease and fall under our radar.

Testing is important, but it’s just one component of a complete disease control program. Working with your veterinarian to develop proper vaccination, biosecurity and bio-containment strategies is required for a comprehensive plan. The long-term goal is always to create the best opportunity to increase, or at least maintain, overall herd efficiencies, health and profitability. PD

Tom Shelton, M.S., DVM, is a senior technical services veterinarian for Merck Animal Health from Washington, Utah. He specializes in calf health and performance, vaccinology and immunology. Michael Coe, DVM, Ph.D., is the vice president of animal health for Animal Profiling International from Logan, Utah. He specializes in health management, nutrition, microbiology and production medicine.

References omitted due to space but are available upon request. Click here to email an editor.